Who Was Blanche Dominick? An archival exploration into gendered legacies of nineteenth century life in the Three Villages.

- archivist97

- Jan 30, 2024

- 14 min read

Updated: Feb 3, 2024

By Scott R. Ferrara, MA RPA

Collections and Exhibition Coordinator

Three Village Historical Society

You will not find a Wikipedia page about Blanche Dominick, and you’d be hard pressed to even see her mentioned in any regional or local histories. It seems that Blanche has all but been forgotten in the written texts of our community’s past. There are no known photographs of Blanche, and her life has all but been a mystery forgotten in time. However, Blanche’s life presents an interesting example of nineteenth century life in the Three Villages, and more so, provides an excellent example of how our personal objects and belongings take on a life of their own, long after we are gone. Today, several objects that once belonged to Blanche and her family survived the passage of time and are held in the Three Village Historical Society’s archival collections. In fact, many of the artifacts in our archives did not belong to great and historically prolific people but rather from individuals and families who lived humbly in our community’s distant past. This project was essentially an attempt to "re-humanize" a set of selected items in our archives. This project rediscovered just one of the people represented in our archival collection, Blanche Dominick, and attempted to understand who she was, long after the memory of her had expired. Blanche’s life is fascinating since, to those around her, she was a granddaughter, daughter, niece, and an aunt but [presumably] never chose to become a wife or a mother – something that would have been expected of a woman in the mid-nineteenth century. Investigating her life provides a fascinating micro-historical case study into women’s lives in nineteenth century Long Island. While some of her identified belongings have survived and have been catalogued, it was only recently that her name and story appeared on our radar.

In 2022, the Three Village Historical Society broke ground on the construction of the Dominick-Crawford Education Center, known colloquially as “The Barn”. This project plans to use the reclaimed wood from the original nineteenth century Dominick-Crawford barn, that was moved from its original location in Old Field, by incorporating the barnwood into the structural and aesthetic design of the newly built education center. Discussions of this project have raised important questions as to the historical importance of the original structure and the lived experiences of the people who once relied on this barn for their livelihood. The historical society’s decision to reclaim this structure has given it new purpose and value to the greater Long Island community. Historically, the Dominick-Crawford barn draws its namesake from the first and last private owners of the barn structure. It is presumed that George Dominick built the barn in 1847 when he purchased the homestead property with his wife Sarah H. Dominick (née Floyd) (Table 1.). This project focuses on just one of the Dominicks’ daughters, Blanche Dominick – an individual seldom seen in the historical record but whose presence survives within the archives. Archival collections, genealogical data, and historical research have uncovered fascinating information about Blanche’s life. This research into her life may help us learn what life was like for a woman in nineteenth century Old Field.

Table 1. Dominick Farm and Barn Deed History

Unmarried Women in Nineteenth Century Rural New York

Archival collections are important because historical research has not traditionally examined many demographics of people and archival materials can provide the necessary information to learn about disparate life experiences in the past. For example, the lives of women in the past were recorded only through their relationships with men, thereby relegating women to secondary roles in the historical record. It was very rare for a woman’s life to have been written about and this has complicated our present understandings and perceptions of the past. One unique fact about Blanche Dominick is that she remained unmarried throughout her life. This was uncommon in her time but certainly not unheard of (Table 2.). Most women in rural communities chose to marry because their married status was clearly defined in society [1]. Blanche’s marital status may help us learn more about the cultural factors that shaped her lived experiences and behavior.

Table 2. Marital Status of the Female Population Fifteen Years Old and Older in New York State in 1855, 1865, and 1875. [2]

Year | Single | Married | Widowed/Divorced |

1855 | 37.7% | 56.4% | 5.9% |

1865 | 34.3% | 58.3% | 7.4% |

1875 | 36.0% | 56.1% | 7.9% |

Women in nineteenth century New York remained single for numerous reasons. Historian Nancy Grey Osterud [3] found that most women in rural New York married before they were 30 years old and that their decision to remain single relied on several voluntary or involuntary factors from courtship strategies to family obligations. For example, if a woman didn’t find any suitors that she found appealing then she could wait until someone better came along. If no desirable suitor came along (within her child-bearing age), the woman would be pressed into marrying someone not so desirable or possibly remain single indefinitely. Osterud [4] argues that nineteenth century women looked to their own family as an example, or rather that the relationships of her parents and family helped “shape women’s sense of what they could and should expect in a husband as well as their sense of what their lives would be like if they did not marry”. Blanche’s father certainly set a high standard for what Blanche and her sister Sarah should settle for. After all, a series of love letters between Blanche’s parents [5] still exists in the archival collection of the Long Island Museum. Blanche’s father, George, moved from his NYC life to become a rural farmer in his wife’s neighborhood and did not remarry after the passing of his wife (which was common during this period). Any suitor that came calling for Blanche or Sarah had best be worth their time. Even though Blanche never married, Sarah did; to a wealthy man named Edward Ridgeway [6].

Another possibility as to why Blanche never married may be due to family obligations. It was often the parents hope that one daughter would stay with the family as a sort of caretaker. Osterud argues that the last daughter to leave home would sometimes be labeled as “less marriageable” as a strategy to keep her home. Parents and siblings would conspire to keep one daughter at home to be the family mainstay and handle domestic and financial affairs of the parents. This system would provide the parents with someone to help with daily life and subsequently “provide their daughter the adult responsibilities she would have had if she were married”; and the social perception of adulthood that often accompanied those responsibilities [7]. Single women in the nineteenth century often did not have the social autonomy one would expect but rather would be expected to care for their elderly parents (or the young)- facing similar social responsibilities as that of wives and mothers. Blanche was born in Old Field, New York on February 4th, 1845. Her family history provides us with an interesting look into her upbringing. Blanche’s matrilineal line is difficult to decipher. While we have the names of her female ancestors, we don’t have their stories- only those of male ancestors. There is little we know about the women in Blanche’s family tree outside of basic genealogical data - but with little information we can still learn something. For example, Blanche’s great grandmother was named Elizabeth Hutchinson and she most certainly lived a difficult life. Elizabeth was six months pregnant when her husband, Richard Floyd of Setauket, died on a trip to West Virginia in 1771. Elizabeth named her son Gilbert Floyd (Blanche’s grandfather). Unfortunately, Elizabeth died in 1778, when Gilbert was only seven years old. Over time, Gilbert became Captain Floyd, captain of the 266 ton, 14-gun, private armed vessel The Boyne [8]. Captain Gilbert Floyd married Sarah DeWitt and together had a daughter they named Sarah Hutchinson Floyd- likely to honor the memory of Gilbert’s mother (Elizabeth Hutchinson). Sarah Floyd (née DeWitt) tragically died in 1822, when her daughter Sarah H. was only three years old. Sarah H. (Blanche’s mother) would eventually marry George Dominick and take on the role of the ‘farmer’s wife’ until her death in 1870. On Blanche's father’s side, her great grandfather Francois Dominique was born in La Rochelle, France in 1736, emigrated to the American colonies, and became a reputable lumbar merchant on Cherry Street in Manhattan around 1771 [9], later anglicizing his surname to Dominick. In 1762, he was registered as a volunteer firefighter in NYC [10]. Francois later had a son named Jacob Dominick in 1785 (Blanche’s grandfather). Jacob remained in the city and listed his occupation as “accountant”, according to court documents in 1819. Jacob’s son, George (Blanche’s father), was born on October 23rd, 1812. Eager to leave the city, George moved to Setauket at only 16 years old and was presumably living under the roof of Captain Gilbert Floyd –George would go on to marry Captain Floyd’s daughter, Sarah H. Floyd. George and Sarah’s romance started as early as 1834 as indicated by a series of love letters written between the two, and later married each other the following year. Their first born was a son named Benjamin Floyd Dominick- named after George’s brother. Later, Blanche was born on February 4th, 1845. Lastly, Sarah was their youngest daughter. In 1846, the last will and testament of George’s father was executed, and George received his inheritance. He likely used this money to purchase the homestead in 1847 and, by 1850 , he became a farmer and proud owner of the newly formed Dominick farm in Old Field. The agricultural census data from the U.S. Census Non-Population Schedules of New York provides more insight into the daily life of Blanche and her family throughout her childhood. On January 15th, 1870 Blanche’s mother died from dropsy, an old term for edema (or massive swelling of limbs). Likely ridden with grief and the reminder of his own mortality, George signed over the family homestead to his two daughters, Blanche and Sarah, in that same year of 1870. George’s brother Benjamin moved into the home sometime between 1865-1870, possibly to help with the farm duties. Then, on August 5th, 1876, George Dominick rejoined his wife.

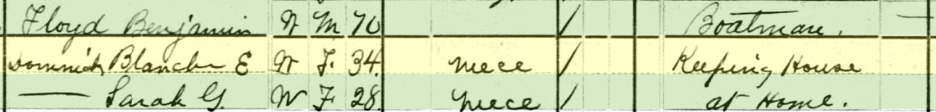

By 1880, Blanche and her sister Sarah were now owners of their childhood home, living with their uncle Benjamin who worked as a “boatman” (Figure 1.). In the 1880 census, Benjamin is listed as the “head of the household”. In this same census, young Sarah’s occupation was listed as “At Home” while Blanche’s occupation was listed as “Keeping House”.

According to the handbook used by census takers in the 1880’s:

“The term "house-keeper" will be reserved for such persons as receiving distinct wages or salary for the service. Women keeping house for their own families or for themselves, without any other gainful occupation, will be entered as “keeping house.'' Grown daughters assisting them will be reported without occupation.” [11]

Even though Blanche and her sister were the legal owners of the home, it was socially required that the head of the household be a male. This practice ensured the household would maintain its perceived respectability within the community – a nineteenth century social norm that has fortunately been abandoned. [12]

Blanche’s life came to an end three years later when she was only 38 years old. She had apparently been suffering from some unknown health condition and died during a surgical procedure in New York City [13]. Her brother, Benjamin Floyd Dominick, recorded in his family bible that Blanche died on November 4th, 1883, in “New York” (Figure 2. & 3.). Other death entries in this bible were recorded as happening in “Setauket”. This implies that Blanche had died in New York City [14]. This is confirmed by her obituary in the Port Jefferson Times published on November 10th, 1883, which reads:

“Miss Blanche Dominick, an estimable young lady of Old Field, who has been au afflicted sufferer for several years past, died at a hospital in New York where she had been induced to go for surgical treatment. The funeral took place at Setauket where the deceased was brought for internment on Thursday last. Miss Dominick was held in high esteem by friends and acquaintances and her departure in early life caused mingled feelings of regret.” [15]

Farm Life According to Census Data

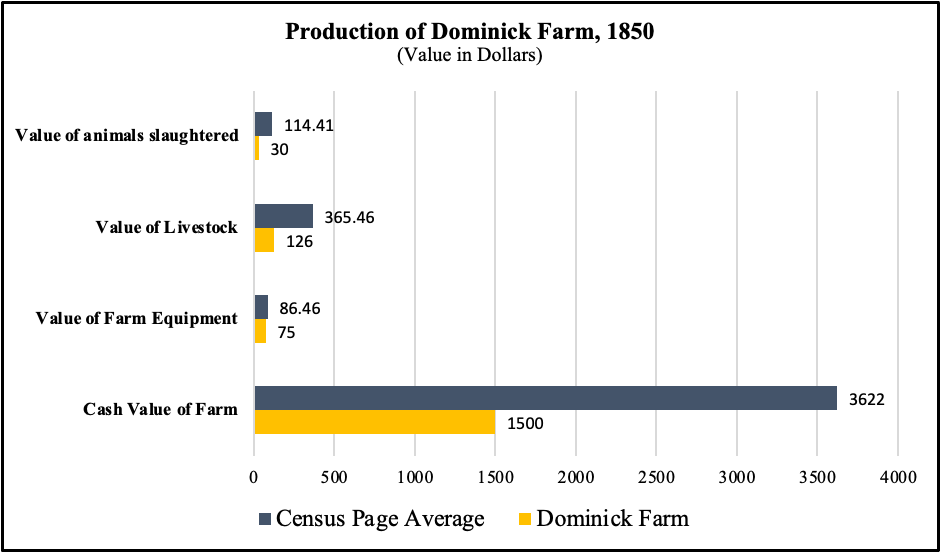

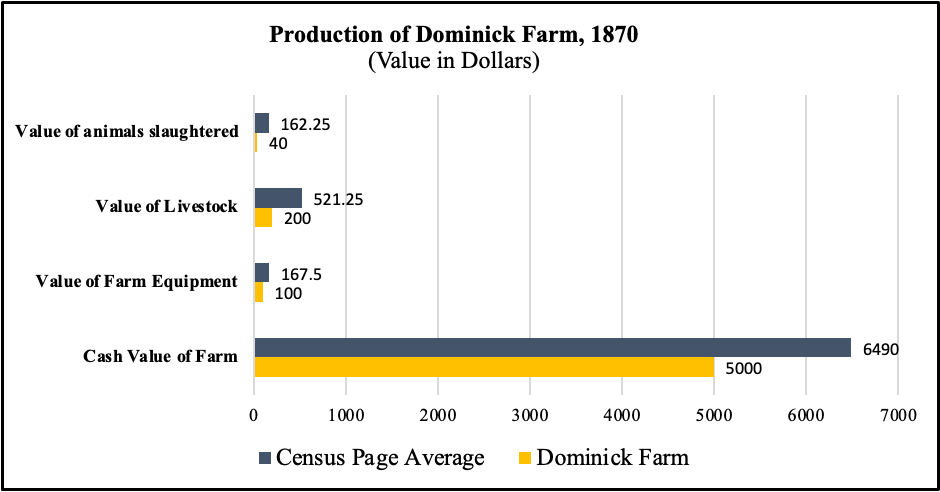

An analysis of agricultural data from the Dominick farm was gathered from state (non-population) census records from the years 1850, 1860, and 1870 [15]. These census recordings were taken every 10 years but only accounted for information of the preceding year. These data show the amount of agricultural goods produced in the preceding year, as well as cash value of the farm and livestock. An analysis of the Dominick farm was conducted by recording the Dominicks agricultural data and production and comparing these data to the average of the census page (their neighbors) ranging from 40-41 neighboring farms listed on a census page each enumeration year.

Table 3. Production of Farm Crops on the Dominick Farm.

[DF: Dominick Farm; A: Average of Census Page]

Table 4. Production of Livestock and Livestock Products.

[DF: Dominick Farm; A: Average of Census Page]

These data indicate that the Dominick Farm was under-performing, or rather they were below the average when compared to the 40-41 farms in their area during each enumeration year. Regardless, the Dominicks had increasing profits decade-to-decade. The Dominick farm was not listed on the 1880 agricultural census indicating that the Dominick’s discontinued in this business and their homestead ceased being a productive farm. It is likely that after the loss of Sarah H. Dominick in 1870 and then George in 1876, their daughters Blanche and Sarah, along with George’s brother Benjamin, decided not to continue in the family business. After all, their uncle Benjamin’s occupation was a “boatman” (not “farmer”) according to the 1880 census and probably didn’t care much for farming. Also, the girls were probably not too thrilled to toil the fields and stables if their uncle wasn’t going to share his equal part of the farm duties. Rural women in nineteenth century New York often beared most of the laborious farm duties [17]-more so than their male counterparts. We might imagine the entire Dominick family assisting in the daily routine of toiling in fields of wheat, maize, oats, and potato. We could imagine a young Blanche milking one of the three milch cows or churning butter, of which the Dominick’s produced a whopping 200 lbs. in 1859. Blanche and her sister Sarah had suffered tragedy and change in the 1870’s and likely chose to rely on their inheritance and whatever support their uncle may have provided instead of rushing back to the fields. Blanche and the Artist

Portable Studio East Setauket, L.I. Dec 19, 1866 To Mrs. General Spinola My Dear Friend; I have received your very kind invitation to be present at the Presentation of Veterans Medal to General Spinola by the City of Brooklyn. It speaks meritorious for the General to be so honored at his own home I may possibly be present. It would be gratifying to see Miss. Blanch E. Dommique surrounded by much brilliancy and pictorial effect. Yours truly, William Sidney Mount P.S. I often mention to my friends that General Spinola was born at Stony Brook in the large farmhouse occupied by the Mount family. |

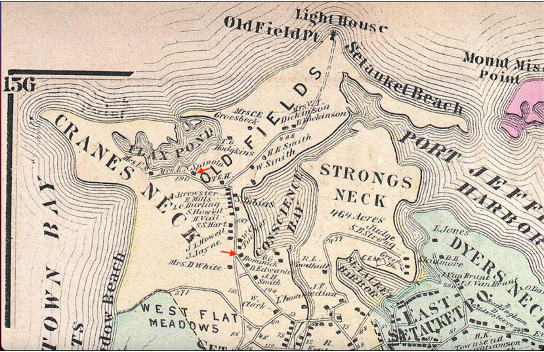

Figure 7. Transcribed correspondence between William Sidney Mount and Mrs. Elizabeth Spinola. A facsimile of this letter is in the TVHS collection. Blanche is mentioned in a letter between genre artist William Sidney Mount (1807-1868) and Mrs. Elizabeth Nancy Spinola (née Glazebrook), the wife of General Francis Spinola [18] (1821-1891). In the letter (Figure 7.), Mount remarks that “It would be gratifying to see Miss. Blanch E. Dommique surrounded by much brilliancy and pictorial effect”. The Dominick’s were neighbors to the Spinolas (Figure 8.) in Old Field and would have known each other well.

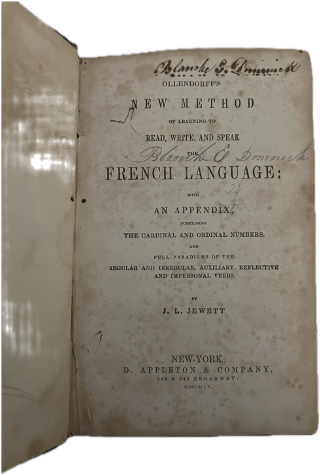

The Spinola’s owned much of the area known as Crane’s Neck in Old Field and while the couple died childless [19], it appears they had some personal relationship with Blanche. Interestingly, Mount refers to Blanche using the last name Dommique or Dominique – the French spelling of her surname used by her family in the early eighteenth century; before anglicized by her great grandfather. Blanche may have culturally identified with her French ancestry and appreciated the gesture of the original French spelling of her surname. Interestingly, one of her surviving personal belongings is a French language textbook (Figure 9.). Mount’s decision to spell her surname in this way may possibly infer a more familiar relationship between William Sidney Mount and Blanche Dominick than has previously been explored.

Later, Mount jotted down in his personal diary:

“Dec 21st [1866] 6 degrees above zero- wind east. This evening, Presentation of Veteran’s Medal to General Spinola by the City of Brooklyn. Mrs. General Spinola at home, Friday evening Dec 21st at 8 o’clock- 3 Livingstone Place, New York. Blanche E. Dominique. It speaks meritoriously for the General to be so honored at his own home” [20]

Mount only jots down Blanches name with no context, as if practicing what to write in the letter to Mrs. Spinola. Nevertheless, his variation in spelling Blanche’s surname between the two documents suggest an intentional decision to use the French version of Dominick. At this time, Mount was 59 years old, and Blanche was 21 years old – both died unmarried. Mount’s motivations for writing this, as well as the nature of his relationship with Blanche may forever be a mystery.

The Legacy of Blanche Dominick

Blanche’s life is a testament to the legacies of mortality. Although we may never truly know who she was, her memory remains through the objects she owned, altered, and left behind. This historical exercise attempted to uncover the life of an individual who might never have been remembered otherwise. Frankly, our archives are important; whether we want to learn more about the most famous Three Village residents or if we simply want to know about the life of a Victorian Era farmer’s daughter. The TVHS archives are a vital community resource that has helped researchers answer questions anywhere from their own family genealogies to understanding global systems throughout the past.

Blanche Dominick may not have been historically prolific but the mark she left behind helps us understand what life was like in the distant, and often forgotten, past. The objects she once used such as barn equipment found in the Dominick barn to a French language book helps us piece together who she was as a young woman living in Old Field.

Further, it had been reported in past decades that a windowpane in her family home still bares the carving “Blanche Dominick” that she had presumably etched in the glass when she lived there. This windowpane etching is quite profound when considering the details of her life. She might have carved this as a young child practicing her name, or while starring out the window pondering her life her future, or maybe to stay connected to her childhood home after the passing of her parents. Quite frankly, we may never know her motivations for making the inscription but the fact it had been noted by the Historical Society and remarked on allows us to see and remember her regardless.

On January 6th, 2024, the Dominick house, now a private residence, caught fire and was quickly responded to by a joint effort between the Setauket and Port Jefferson Fire Departments. The extent of damages to this historic home and the condition of Blanche Dominick’s inscription is currently unknown. However, this sobering example shows how delicate the historical resources are in the community and how important their preservation is. The historical and cultural resources of the Three Village area help to shape our heritage and memory of the past.

So, what happens after we pass away? What memory of us will survive after the last person who knew us fades away. Blanche Dominick’s life is a testament to our purpose as an historical society. That our memory will not only survive but be safe-guarded, and help others learn about what life was like in our respective times. Everyone’s story matters and there is something to learn from everyone’s life. Even when the last person to remember us passes away, you too may live on in the archives of the Three Village Historical Society.

Notes

[1] Nancy Grey Osterud, Bond of Community (1991), 123. [2] Data from Vinovskis “Marriage Patterns in Mid-Nineteenth-Century New York State” Journal of Family History 3, no.1 (1978), 53. [3] Nancy Grey Osterud, Bond of Community (1991), 123. [4] Ibid,124. [5] These love letters date from 1834-1856; starting a year before George and Sarah Dominick were married. [6] Despite Edwards fortune, he still agreed to move into Sarah’s childhood home-maintaining the Dominick property.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Information from US Office of Naval Records and Library.

[9] Lyman Horace Weeks, Prominent Families of New York, (1898), 185.

[10] J. Frank Kernan, Reminiscences of the Old Fire Laddies (1885), 886.

[11] See “Appendix A. Instructions to Enumerators Concerning the Return of Occupations at the Censuses of 1870, 1880, 1890, and 1900”. Statistics of Occupations. Pg. ccxlviii.

[12] According to a recent research survey, in 2022 single women were more likely to be home owners than single men. Pew Research Center.

[13] Perhaps related to her family medical history- as dropsy had afflicted her mother who died at 51 years old.

[14] The Benjamin Floyd Dominick Family Bible is in the TVHS collections.

[15] Port Jefferson Times Obituary, 10 Nov 1883.

[16] Census data retrieved from Ancestry.com

[17] Nancy Grey Osterud, Bond of Community (1991), 142.

[18] General Francis Spinola was the first Italian American to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. [19] Arthur L. Douglas Jr., A Short History of Crane Neck (1979), 11.

[20] Alfred Frankenstein, William Sidney Mount (1975), 43.

References:

Douglas Jr., Arthur L. 1979. A Short History of Crane Neck and the Crane Neck Association. The Crane Neck Association, Inc. Old Field, New York. Photocopy on file at the Three Village Historical Society archive- Genealogical collection.

Frankenstein, Alfred. 1975. William Sidney Mount. Abrams. New York, New York.

Kernan, J. Frank. 1885. Reminiscences of the Old Fire Laddies and Volunteer Fire Departments of New York and Brooklyn. M. Crane Publisher. New York, New York.

Osterud, Nancy Grey. 1991. Bond of Community: The Lives of Farm Women in Nineteenth Century New York. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, New York.

U.S. Office of Naval Records and Library. 1935. Naval Documents related to the Quasi-War between The United States and France: Naval operations from November 1798 to March 1799. United States Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C.

Vinovskis, M.A. 1978. Marriage Patterns in Mid-Nineteenth-Century New York State: a Multivariate Analysis. Journal of Family History 3(1):51-61.

Wall, Diana Dizerega. 1999. Examining Gender, Class, and Ethnicity in Nineteenth-Century New York City. Historical Archaeology 33(1):102-117.

Weeks, Lyman Horace. 1898. Prominent Families of New York. The Historical Company. New York, New York.

Random Name Generator is a well-known online tool that blends utility, creativity, and simplicity into a straightforward but effective experience. The user interacts with the generator to instantly produce unique and fitting names for characters, projects, or creative endeavors in this tool.

Drift Boss is a well-known online game that blends precision, rhythm, and excitement into a straightforward but addictive experience. The player steers a car around an endless, winding road, aiming to perform perfect drifts and stay on the platform in this game.

best iptv : Welcome to Best IPTV 4K, your number one destination for premium-quality IPTV streaming. We bring you the future of television — thousands of live channels, movies, and series available in crystal-clear 4K Ultra HD. With lightning-fast servers, a smooth user interface, and zero-buffering performance, Best IPTV 4K ensures that your viewing experience is seamless and enjoyable every time.

Whether you’re a fan of live sports, movies, international channels, or entertainment shows, we’ve got you covered with a vast and diverse selection of content from all around the world. Our service is compatible with all major devices — including Smart TVs, Android boxes, Firestick, and mobile devices — making it easy to enjoy your favorite programs anytime, anywhere.

At…

What a fascinating deep dive into forgotten local history — rediscovering lives like Blanche Dominick’s truly brings humanity back to archival work. It’s amazing how artifacts can speak long after their owners are gone. That same sense of uncovering hidden stories and eerie echoes of the past reminds me of Five Nights at Freddy’s — a chilling game where the past lingers in unexpected ways, waiting to be uncovered piece by piece.

It's fortunate that these objects remain intact through time. This project helps connect the past with the present, just like the Sprunki Game community is always enduring.